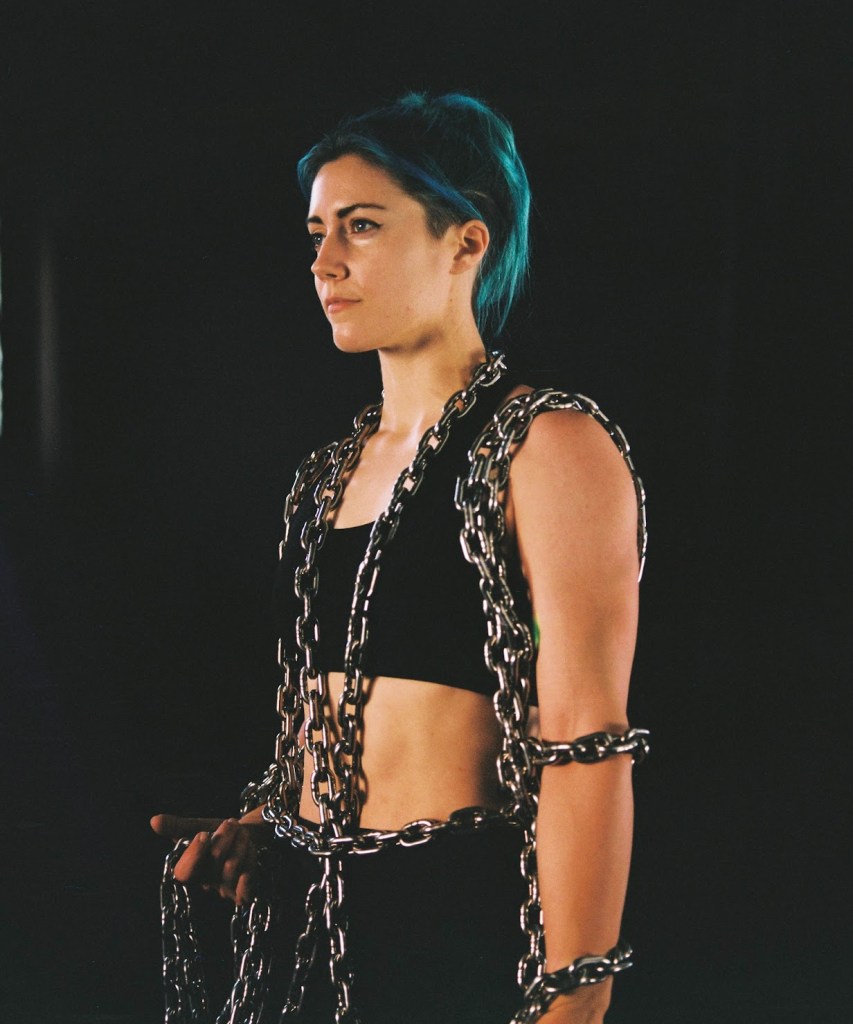

Melissa Ashley Hernandez

August 15th, 2023

Minna Zallman Proctor is an editor, award-winning translator, and writer. She is the author of the essay collection Landslide: True Stories (Catapult, 2017), Do You Hear What I Hear? (Viking, 2005), and co-author with Bethany Beardslee of I Sang the Unsingable: My Life in 20th Century Music (University of Rochester Press, 2017). Her recent translations from Italian include Fleur Jaeggy’s These Possible Lives (New Directions, 2017), and Natalia Ginzburg’s Happiness, As Such (New Directions, 2019), shortlisted for the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation and longlisted for the PEN Translation Prize. Her translation of Cesare Pavese’s existentialist interpretation of Greek myths, Dialoghi con Leucó, is forthcoming from Archipelago. She has written for Bookforum, The American Scholar, Conjunctions, The Nation, Aperture, NPR.org, The New York Times Book Review, and others. She has been an editor at COLORS magazine, BOMB, and The Literary Review. She teaches in the creative writing program at Fairleigh Dickinson University. She is currently working on a collection of short stories responding to Pavese’s myths and a new translation of Fabrizia Ramondino’s Althénopis for New Directions.

Minna Zallman Proctor cannot be summed up into words. She is an ethereal and unending fountain of joy and wisdom and is monumentally skilled at her craft. She gave me the opportunity to pick her brain about mythology and folklore, and I left with more questions than before! Differences between mythology and folklore can sometimes be nebulous and in many cases subjective, but we still had a great time discussing ideas and hypotheticals.

(You can read Volume 3 of Mythological Minison here tomorrow!)

Interview with Minna Zallman Proctor

The Minison Project: There’s so much to cover, let’s just jump right in! What is your relationship to folklore and mythology?

Minna Zallman Proctor: The first thing I think of when you ask this question is that when I was a little kid I never went through the big Greek/Roman Gods and Goddesses stage that a lot of kids go through. I did a report on Herakles when I was in fourth grade and I was really intrigued by the concept that all the stories came from urns—which they didn’t but that was interesting—and I always believed the interesting version of truth over the real version. Other than that, I liked Irish folktales Arthurian legends, Norse mythology, and African folktales, because those were the books I found on my parents’ bookshelves. The Irish folktales were in a book that I loved especially called There Was a King in Ireland and all the stories (obviously) started, “There was a King in Ireland…”

But that’s my formative/little kid relationship to myth. My interest in the African folktales stuck the longest, because they were all short and profound and funny—like the one about how the sun went to live up in the sky because he was annoyed about the way people kept breaking bits off of him for an afternoon snack. Caveat: the book I read from was edited by Paul Radin, a Jewish immigrant from Poland who was an influential anthropologist in the 1950s who specialized in Native American and African religion and language. I suspect that a great deal of his work and probably all his cultural perspective has since been invalidated.

Then I didn’t think about myths at all for a long time. …until I started work on this translation project about Greek mythology, and suddenly that’s all I think about.

TMP: I suspect that a lot of the obsession for Greek and Roman myths stem from focusing on those literatures in schools, so I find it fascinating that you discovered Norse and African folktales to be more captivating for you. With that and everything you’ve been researching for your translation project, which I’ll ask about later, how would you classify the differences between folklore and mythology?

MZP: I am 170 percent sure that there is a formal distinction in the social sciences, which I don’t know and won’t look up, because it’s more fun to guess and make up an answer. So, with the caveat that I’m inventing this: Mythology explains things—why the grass is green, where you go after you die, why we exist. Mythology is exalted, larger than life, aspirational and eternal. Folklore are stories authored by a community—stories that are passed down whose purpose is story, nothing more or less. Folklore is local and specific and only lives as long as people repeat it. Both mythology and folklore are author-less. This is important. They belong to time and place, but not a single intelligence. Because folklore is specific, it reveals details about very specific cultural systems… of a family, of a village, of a town. Mythology is more general with an eye toward universal, and the figures of mythology are avatars; there is nothing really substantial in their character build that determines their actions; there are no real individuals; the gods have many faces and many names—suggesting they are many but none. Folklore is the language of a people. Mythology is more of a code than a language, and as such has a broader reach. This shared code crosses lands and histories and cultures and timelines. We continue today to repeat and interpret those ancient mythologies bringing them forward organically from a long long time ago to now. Roland Barthes said the mythologies a society creates express explanation and desire and that determines, and codifies, values.

And again, I just made this up. There are actual, formal definitions in some fields and volumes of theories and debates too. In other words there’s a 100 percent probability that there are many answers to this question that contradict, or at least discredit, mine.

TMP: You said “folklore is local and specific,” but when people document folklore on the internet where it can be widely spread, does it lose specificity and context? And what role do you think technology has played in allowing these stories to reach beyond their regional communities?

MZP: That’s such an interesting question and I wish I had a very smart answer. …In discussions of the internet, people reference this participation inequality ratio: 90 percent of users are “lurkers” (aka “audience”), 9 percent occasional participants, and 1 percent create all the content. (This ratio is over fifteen years old, so it has likely shifted as social media has grown.) In really crude terms, participation inequality is bad because it means that one percent of people have “undue” or “outsized” influence. But the same ratio applies to wealth (the “one percent”), and we know that wealth isn’t just having more, it’s about controlling more and so everything that’s about control—legislation or information—is basically controlled for all by the very few. Which is sinister and antidemocratic and totally from the dark ages and all of this has happened before and all of this will happen again. But, there is something about that ratio that also calls to mind a group of people gathered around a storyteller. Yes, folklore is of a community and is not about authorship, and yet, it’s not as if the village gathered for storytime and then everyone started talking at once. That’s anarchy, not folklore. When everyone on the internet is talking at once and no one is listening, then everything zeroes out and is totally useless. (Like, if you’re looking for a restaurant on Yahoo and it has 800,000 reviews, you know you’re not going to learn anything about whether to go to that restaurant from the reviews: half the people hated it and half of them loved it and half of them hated it for dumb reasons, like it was raining the night they went, and the other half of them hated it for good reasons that are meaningless to the other half of the people—like, say, the ketchup was too vinegary, which is meaningless because half the people hate ketchup and wouldn’t order it anyway, and half the people prefer their ketchup more vinegary, and half the people wonder “How much is too much?”… so that’s just time wasted.) I guess what I’m saying is that folklore is by definition unauthorized, it’s passed along by people and may be altered in the process for any number of reasons. If it’s being passed along on the world wide web instead of in a town square, the people who receive it to pass it along might evolve it differently than the people who receive it and repeat it in the town square, but that just means that there are now different evolutionary tracks (probably many many different ones) for that story. Some are more local than others. Consider this, the African folktales I read in the 1970s were collected in the 1950s, translated by one person from a variety of languages and cultures into a monolithic text, and published in a book, which fixes a story in that moment and culture and medium. It un-folklores it. In other words, is the world wide web essentially more pernicious than 20th century ethnographers? Probably yes, and probably no. …Maybe it depends on whether you like ketchup.

TMP: “Un-folklores” is such a good term. You bring up a good point: when everybody is talking at once, can anybody really be heard? I often wonder about our future and our legacy as human beings. Do you think any modern stories will be classified as mythology or folklore in the future?

MZP: I don’t know. The question is really about whether we human people have hit some natural limit of archetypes, or explanatory apparatus (e.g., Why is the sky blue? Where does water stop? Why do we exist?) Are there things in the natural world that don’t already have a variety of explanations versatile enough so that the stories start repeating each other? Will we change the natural world so much that we’ll need new explanations? And, in terms of being worried about our future because we’re always challenging and disrupting the natural world, don’t you think it’s significant how many morality tales in mythology and folklore turn on the sin of hubris (aka pride)? …Maybe that’s because humanity keeps moving toward its own eradication with progress, and recklessness? And then it explodes and starts again, or the gods throw rocks and destroy and rebuild? It’s been and will be again, etc. Why does Prometheus’s liver keep growing back so that the birds can eat it again? Will AI ever be so mysterious that we’ll need to explain it in terms that go beyond “manmade”? Can AI turn into organic matter? And, if so, is that how the earth ends and restarts? Is bacteria AI? Will the new organic AI need explanations about how it came to be, or will it just access its vast information banks and discover that it was created out of 1s and 0s by people who were created out of cell division? Do you think, maybe, that aliens/life on other planets will be our future folklore? Or, do you think that the idea of other life forms on other planets is another variation on the idea that gods live in the sky? Was Zeus an extraterrestrial? And, I want to know about sharks.

TMP: I think we all want to know about sharks… Do you think folklore is a building block to creating mythology or does mythology spawn folklore?

MZP: I think they are two kinds of storytelling that both have strong cultural roots and identities. Whether you’re using my explanation above or Carl Jung’s, the distinction between myth and folklore is artificial; it’s either descriptive or theoretical—like the distinction between poetry and prose. It’s not as if you’re describing mitochondrial division, or the difference between sand and glass. Sure there’s overlap and fuzzy boundaries. (Is a story about how the leopard got its spots a local morality tale or a cosmology?) Different cultures express different needs and wants through the stories they tell. But ultimately storytelling has its origins in rational thought. The question Why? is the primordial ooze of language. Event and consequence are the primordial ooze of story. Those are the building blocks; mythology and folklore are some very big buildings those blocks made.

TMP: Let’s talk a bit about your translation project! What’s that about?

MZP: My translation project is hard to explain. Every time someone asks me about it, I talk for an hour too long. I have to find a compact way to describe it. Like everything complicated, it starts, of course, with my mother. My mother was fascinated with this book, which in Italian is called Dialoghi con Leucò, and its author, Cesare Pavese, who was mostly a poet and novelist—even though this book is not really either. I’m chronically fascinated by my mother, who was a composer, whose music was inspired by literature. When my editor at Archipelago and I were casting around for a perfect new project—and she was making some wonderful, very fun suggestions—then I had this image of my mother holding this particular book, and I asked if maybe it could be the perfect project. Ultimately, it wasn’t a perfect project; it was something else. More like a dare. The hardest thing I’ve ever translated. Baffling on every single level, from the subject matter to the language, to the emotional center, its socio-historical context, the conceptual landscape, the legacy. I love it unreasonably now, but I think that’s because I finished it.

Here’s my attempt at a compact description: Dialoghi con Leucò is a collection of 27 short lyrical dialogues between Greek gods and heroes, reimagined as existentialist debates, the paradoxes of which are extrapolated from their big mythological stories: Oedipus wondering whether the choices of his life have any moral meaning at all if they were all prophecy. Calypso trying to convince Ulysses that immortality is just as good as mortality—because she loves him and wants him to stay with her, but she doesn’t quite believe her own argument and he sees through her. Endymion complaining because his rapist, Artemis, won’t let him love her back. Leucothea (the white goddess) trying to convince Ariadne that she should stop crying about Theseus abandoning her, because Dionysius loves her and is going to turn her into a constellation—a cold comfort. Sappho hating the afterlife, because it exists, and she had killed herself to stop her thoughts, not to sit in them for eternity. And so on. They are funny and brutal and complex and suffuse with contemplations of life and death.

TMP: That sounds right up my alley, I can’t wait to read it! Is there anything you wish I asked that you would like to talk about?

MZP : ….Melissa, you’ve asked me everything there is to ask in the world and many things that I don’t have answers for. I’ve been thinking about myths in such a specific way for the last three years, and it’s been very fun to think about myths and folklore from a more holistic, cultural perspective for this interview. There’s a reason we all come to myth with different questions and wildly different answers, and the reason is routed in myth as a common point of reference. In his foreword to Dialoghi con Leucò, Pavese wrote: “Given the option, a person could certainly get by with less mythology. But we’ve come to accept mythology as a language, an expressive mode—which is to say, it’s not random, it’s a hothouse of symbols that belong, like all languages do, to a specific set of references that can’t be conveyed any other way.”

MYTHOLOGY LIGHTNING ROUND:

TMP: What is your favorite myth?

MZP: Orpheus

TMP: What is your favorite folktale?

MZP: The Devil

TMP: Which mythological figure do you relate to most? Who do you find most interesting?

MZP: Circe

TMP: Which mythical creature would make the best pet, and why?

MZP: Heracles. I think he’d be good at protecting me.

TMP: In mythology or folklore, if you could swap the roles of a hero and villain, who would you switch and why?

MZP: …I don’t know. I think one of the cool things about mythology/folklore is that all the archetypes are both good and bad or value-neutral or undeclared. Like the idea of a “trickster god” for example, or Dionysius, who’s fun, and fun-loving, and dreadful, and a savior, and a killer. …PASS

TMP: Is there any country’s mythology or folklore that you haven’t explored yet that interests you?

MZP: Of course—it’s not like you finish being interested in something you don’t know everything about. The list is inexhaustible. But. …if I had to pick two (because one is totally not possible), maybe I’d say Poland and Brazil.

A huge thank you to Minna for granting us the time to conduct this interview! If you’d like to support her, you can visit her website here and read her work.