Ada Wofford, Senior Editor

April 22nd, 2021

Part Four

In this installment, I look at some of the criticisms of Instapoetry, including my own. I also pull from establish critics and academics, such as James Longenbach, because I want to illustrate the broader conversation on poetry that I am participating in when I write about Instapoetry— these are books I read and things I learned as both a student and a writer and I point them out, not to disrespect them or denounce them in anyway, but to highlight my thought process and to specify what ideas I’m attempting to push up against in my own work. The work of critics like Longenbach and Rebecca Watts is an invaluable contribution to the larger conversation surrounding poetry and literature and I see my writing as building off of their work, not as an attempt to blanketly refute it.

Rebecca Watts’ article, “The Cult of the Noble Amateur” is a scathing tirade against contemporary popular poetry, including, but not limited to, Instapoetry. Watt’s opening paragraph really sets the scene:

Why is the poetry world pretending that poetry is not an art form? I refer to the rise of a cohort of young female poets who are currently being lauded by the poetic establishment for their ‘honesty’ and ‘accessibility’—buzzwords for the open denigration of intellectual engagement and rejection of craft that characterises [sic] their work. (13)

There are lots of things to take issue with here. What exactly is the poetic establishment, and is it something we should even care about? Then there’s the question about the definition of intellectual engagement: What is it and why is it so necessary in order for a work to be deemed worthwhile? And whose intellectual engagement are we talking about? As Milton writes in Aeropagitica, “[. . .] a wise man like a good refiner can gather gold out of the drossiest volume, and that a fool will be a fool with the best book.” If Watts cannot find something to appreciate in this new form of poetry, is it fair to ask if it’s her own fault? But to Watts’ credit, however good a refiner you might be, Instapoetry doesn’t give you much material to refine. Watts quotes Kaur’s publisher, Kirsty Melville: “[. . .] the medium of poetry reflects our age, where short-form communication is something people find easier to digest or connect with” (13). This makes sense, but does it make good poetry?

In my essay on Kaur, I critiqued this untitled poem from milk & honey (there is a visual component to this poem that I am not concerned with but will describe here for the reader: underneath the text is a line illustration of two hands reaching up):

how can i write

if he took my hands

with him (121)

I used this poem to point out Kaur’s lack of rhythm and meaningful line breaks. My analysis of this poem was principally informed by James Longenbach’s book, The Art of The Poetic Line, in which he writes: “More than meter, more than rhyme, more than images or alliteration or figurative language, line is what distinguishes our experience of poetry as poetry, rather than some other kind of writing” (xi). I took this sentiment to heart and walked my readers through my own rewrite of Kaur’s poem; one that paid attention to stresses, scansion, and above all, the use of line-endings (line-endings is Longenbach’s preferred term). Although somewhat lengthy, I am going to reproduce this aspect of my essay here because it perfectly illustrates what I now believe is an artistic crime (on my part only. Longenbach is not guilty of this. I applied what I learned in his book in a manner I now disagree with). I will bold the phrases I now find particularly problematic as they should prove useful in our discussion going forward:

In his discussion of line-endings, Longenbach writes, “But even the arbitrary must be driven by necessity, and necessity can be judged only on a poem-by-poem basis: what does the language of this particular poem require at this particular juncture?” (63). If we look at the use of syllables in the above poem we get, 4, 5, 2. There’s nothing to suggest this was done purposefully or out of necessity. An examination of the use of stresses tells the same story—Nothing appears deliberate or driven by necessity. The only remaining conclusion is that the line-endings are done purely as a visual component. This is reinforced by Kaur’s deliberate choice to eschew punctuation and capitalization with no apparent meaning behind this choice, save for the previously mentioned visual component.

To gain a better understanding of Kaur’s poetry, it’s worthwhile to explore what this poem would look like if we attempted to inject some poetic elements into it, such as attention to syllables and stress. By introducing syllabic-verse the line-endings will become more meaningful.

How can I write

If when he left

My hands he took

It’s still sloppy but at least it has rhythm, purposeful use of syllables, and it no longer has that clunky enjambment at the end. The reason this is better than the alternative, “If when he left/he took my hands” is that now “he” is the second to last syllable in the last two lines. But we can still improve it:

How can I write

If when he left

My hands he kept

Now there is more information in the poem and “left” pairs nicely with “kept,” both having the same vowel sound. All three lines function as pairs of iambs now as well. As for context, it is now made clear that the narrator had given her hands at some point in the past. In the context of the entire book we can infer that she at some point gave her hands to a lover, but in the context of the original poem we are not given enough information.

The big issue with this poem, really with most of Kaur’s poems, is that it goes nowhere. It makes a singular statement, “He took my hands and now I can’t write.” And when I rearrange this to introduce rhythm into the writing it’s like hearing a melody that never resolves itself. Just as the rhythm gets established, the poem is over. It becomes obvious from this exercise that a poem this short actually suffers from the inclusion of classic poetic elements. Now, instead of having a short poem with no rhythm, we have a rhythmic poem that feels incomplete. (“Understanding”)

I refer to this as an artistic crime because there’s absolutely no need for it. I’m not writing a poem inspired by Kaur’s poem, which is something many poets do—No, I’m tearing it to shreds in the name of “proper” poetry. I claimed that my modified version is “better” and that I can “improve” it further as if an objective good existed in poetry. In his introduction to Russian Formalist Criticism, Gary Saul Morson writes: ”Jakobson wrote that ‘poetic form is the organized coercion of language’ (quoted in Eichenbaum, 127), that is, it is ‘practical’ language deformed into poetic language” (Lemon, loc-189). This is exactly what I was attempting to do with Kaur’s poem: deform her practical and ordinary language into a “poetic language.” And while the Russian Formalists, Harold Bloom, and others all believe there to be a strict distinction between poetic language and ordinary language, no one can agree on a single definition.

Despite the ambiguity of the term poetic language, it’s a widely held belief that poetry needs to be informed by academia. In preparation for writing this essay, I posted a question on all of my social media accounts: “For a research project: Do you enjoy Rupi Kaur and the genre of Instapoetry? If so, why? What do you get out of it? Why is it valuable?” Granted, I’m involved in the literary community and know many editors, poets, and writers but not everyone who replied exists in these circles. I did not get a response from anyone who really enjoyed Kaur or Instapoetry, but some were appreciative of the fact that it’s getting people into poetry. One poetry editor and teacher commented, “[. . .] While I rather loathe it myself, I’ve met too many students who love it and came to poetry through that doorway to dismiss it entirely.” Two poets I know, both pursuing their MFA, commented their disdain for Kaur, saying her poetry lacks depth and that, “Reading her is like nails on a fucking chalkboard.” One commenter, who works in computers (i.e. not involved with the literary community or with the academy), referred to Instapoetry as an inevitable evolution of poetry due to the way we now consume information. While they do not personally see the appeal of this genre, they thoughtfully added, “If it makes people feel something and they connect with it in a way they find meaningful isn’t that valid?” This sentiment contrasts nicely with a comment from an MFA student who admitted that Kaur is highly successful but added, “[. . .] it’s not like she’s going to win some kind of major book award.” This brings us back to the academy and Watts’ “poetic establishment.”

Who Gets to Write Poetry?

This is the essential question at the heart of this debate. One of Watts’ issues with contemporary popular poetry is that anyone can do it (15). But why is this a problem? Furthermore, why is there such an emphasis on complexity or difficulty? The most troubling thing I said in my critique of Kaur was that “It becomes obvious from this exercise that a poem this short actually suffers from the inclusion of classic poetic elements” (“Understanding”). When I wrote that, I knew it wasn’t true and why I didn’t take the time to qualify that statement I’ll never know. What I should have said, is that a very short poem can suffer from the particular poetic elements I was working with (stress, scansion, line-endings). William Carlos Williams’ poem, “The Red Wheelbarrow” is the perfect example of a poem being short and simple yet critically acclaimed:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens. (56)

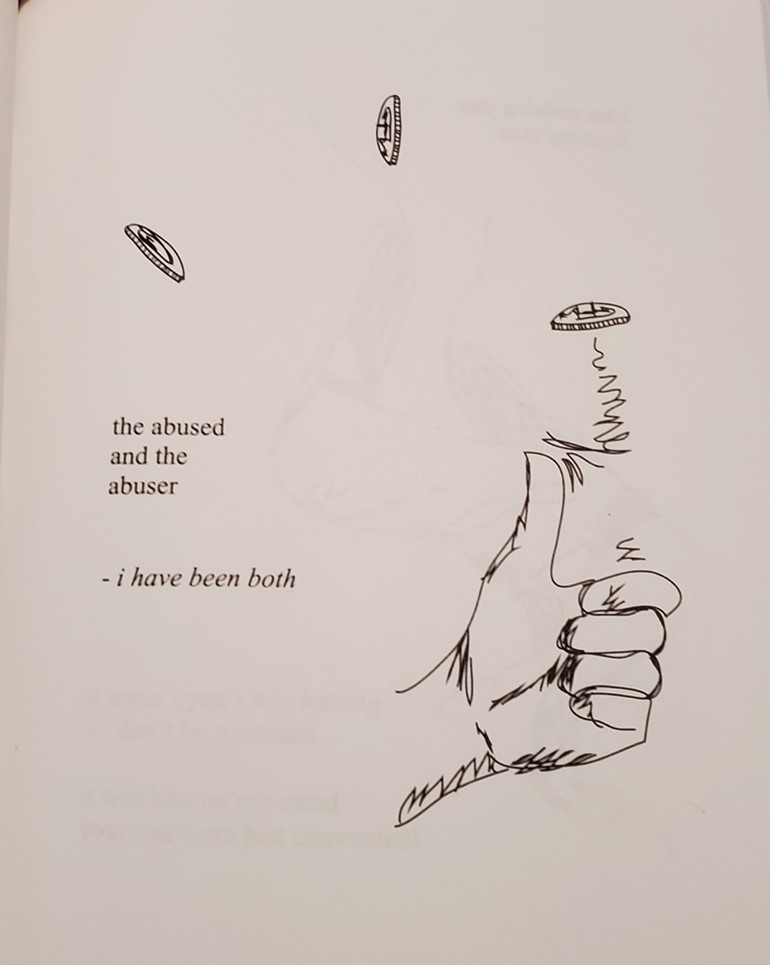

I made a point to format Williams’ poem exactly how it is in the book because formatting is an essential part of all visual poetry All written poetry is visual poetry, but some poems utilize this element more so than others. Reading this poem, it seems to me that Williams’ line-endings are primarily motivated by this visual element. The poem looks very balanced and clean. The line-endings can be said to convey meaning by emphasizing certain words, but they do not function rhythmically as emphases, at least not to my ear. This poem is a single sentence divided into four stanzas or sections consisting of varying syllables (6,5,5,6), which create a certain symmetry but not necessarily one you can hear. The poem certainly has a rhythm to it but nothing formal or precise. In other words, this reads as “practical language” but it is not framed or presented as practical language. The poem’s minimalism emphasizes the minimalism of the scene itself and highlights the importance that everyday objects can have to us. But why is this poem so widely celebrated in the academy while Instapoetry is shunned? Compare it to this untitled poem by Kaur:

for you to see beauty here

does not mean

there is beauty in me

it means there is beauty rooted

so deep within you

you can’t help but

see it everywhere (192)

Right away, we can see that there is not as much attention to formatting or to the visual balance of the piece, though Kaur does create a nice symmetry in the structure of the lines (3,1,3). The number of syllables appears arbitrary (7,3,6,8,5,4,5) and the line-endings don’t emphasize a particular rhythm, though there is the symmetry of “beauty here” and “beauty rooted.” The first three lines set up the issue or concern and the last three provide the explanation. This pair of three-line sections pivots on the center line that connects the issue and explanation. The rhythm might not be as smooth as Williams’ but there is still some rhythm to it. The two most important similarities between these two poems is the use of minimalist technique and ordinary or practical language.

Despite these striking similarities, one is considered a classic of American poetry and the other is considered mediocre pop culture. Even I admit, something about the Williams’ piece moves me in a way the Kaur piece does not. I personally prefer writing that looks outward at the world and interrogates the quotidian (such as focusing on a wheelbarrow), but many others who do not share my preferences also despise Kaur’s work yet appreciate Williams. I do not think it is the subject matter of Kaur’s poetry that elicits such negative responses as so much of contemporary poetry is focused on the self, the body, identity, trauma, and growth; and all of these themes are front and center in Kaur’s work. But I don’t think it is Kaur’s lack of “poetic language” being used that upsets people either. I think most people (myself included, at least before my recent conversion) share in Watts’ disdain at the idea that poetry is something that “anyone can do” (15).

Gatekeeping like this is similar to what Theodor W. Adorno discusses in regard to musicians in his article, “On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening.” Not only does Adorno lament the supposed death of the listener as Watts laments the death of the reader, he criticizes the idea of people attempting to learn to play music for fun as opposed to devoting their entire lives to the study of music:

In the piano scores of hit songs, there are strange diagrams. They relate to guitar, ukulele and banjo, as well as the accordion—infantile instruments in comparison with the piano—and are intended for players who cannot read the notes. They depict graphically the fingering for the chords of the plucking instruments. (290)

Adorno is eviscerating the way I and millions of other people began playing their instruments. While Adorno had his Marxist motivations to fuel his fear of the “dumbing down” of the masses, this passage paints Adorno as nothing more than an uptight snob who is frustrated by the fact that not everyone is as smart as him. Kurt Cobain learned to play guitar by reading the strange diagrams Adorno speaks of and went on to change the history of rock music. Granted, Adorno would consider rock music “light music” (that which is inferior to “serious music,” which basically means classical music, though he loathes that term). But whether or not some snob in the academy appreciates Cobain’s music, it will never change the fact that his music and his lyrics have touched millions of individuals and positively impacted their lives.

If Shakespeare is to poetry what Mozart is to music—Or, more simply, if what the academy considers “proper poetry” or canon poetry is the equivalent to what Adorno considers, “serious music,” then Instapoetry is what Adorno would call, “light music.” Interestingly, the popularity of this “light music” owes itself in part to the rise of the radio—Just as this new form of poetry owes its popularity to the rise of Instagram and social media sites as a whole. Adorno loathed “light music” and the rise of jazz just as critics like Watts loath Rupi Kaur and the rise of Instapoetry. Of course, jazz and rock are now part of the academy. There’s even an academic journal called Rock Music Studies that features articles analyzing rock albums the same way any literary journal features articles analyzing novels and poems. I believe the most valuable thing we can do as academics is to stop being snobs and focus our attention on how Instapoetry functions and what readers are getting out of it.

In our last installment, we will dig into just how Instapoetry functions and wrap up the series by looking at the future of Instapoetry.

You can follow Ada Wofford on their Twitter: @AdaWofford.